We had a chance to ask Whiti Hereaka some questions:

Q: Why do you write, what is your motivation and what do you hope to achieve through your writing?

A: I write to make sense of the world. Generally I write about something or a behaviour that bewilders me and try to figure it out that way. Sometimes I write to see if I can figure out a puzzle — a form or genre of writing that I’m not familiar with or a set of restrictions I’ve given myself. I don’t really have a motivation, writing is something of a compulsion. What I hope to achieve is a story that works! A story that agrees with its own logic and rhythm. If I achieve anything external to that it is a bonus.

Q: Are there any authors and/or playwrights who have influenced your writing?

A: Plenty! But personally I’ve learnt a lot about playwriting from Hone Kouka, David Geary and Ken Duncum. I was lucky to be mentored during my first novel by Renee and Philip Mann. Witi Ihimaera was – and continues to be — a big inspiration not only in writing itself but in pursuing a career in it. Pip Adam and Elizabeth Knox are always great to knock ideas around with. The writers I’ve only met through their works: Tom Stoppard, Samuel Beckett, Caryl Churchill, William Shakespeare, John Milton, Douglas Adams, Shirley Jackson... and probably whomever I’m reading at the time you ask me (currently Bora Chung)

Q: What do you need in your writing space to help you stay focused?

A: I’m not sure, but if one day I find the magical thing that keeps me focused I’ll let you know. Now I work on guilt about looming deadlines, tea and bribing myself with chippies and chocolate.

Q: What is your least favourite part of the writing process?

A: Some days, all of it. It’s hard to face a blank screen and to open yourself and be authentic and vulnerable.

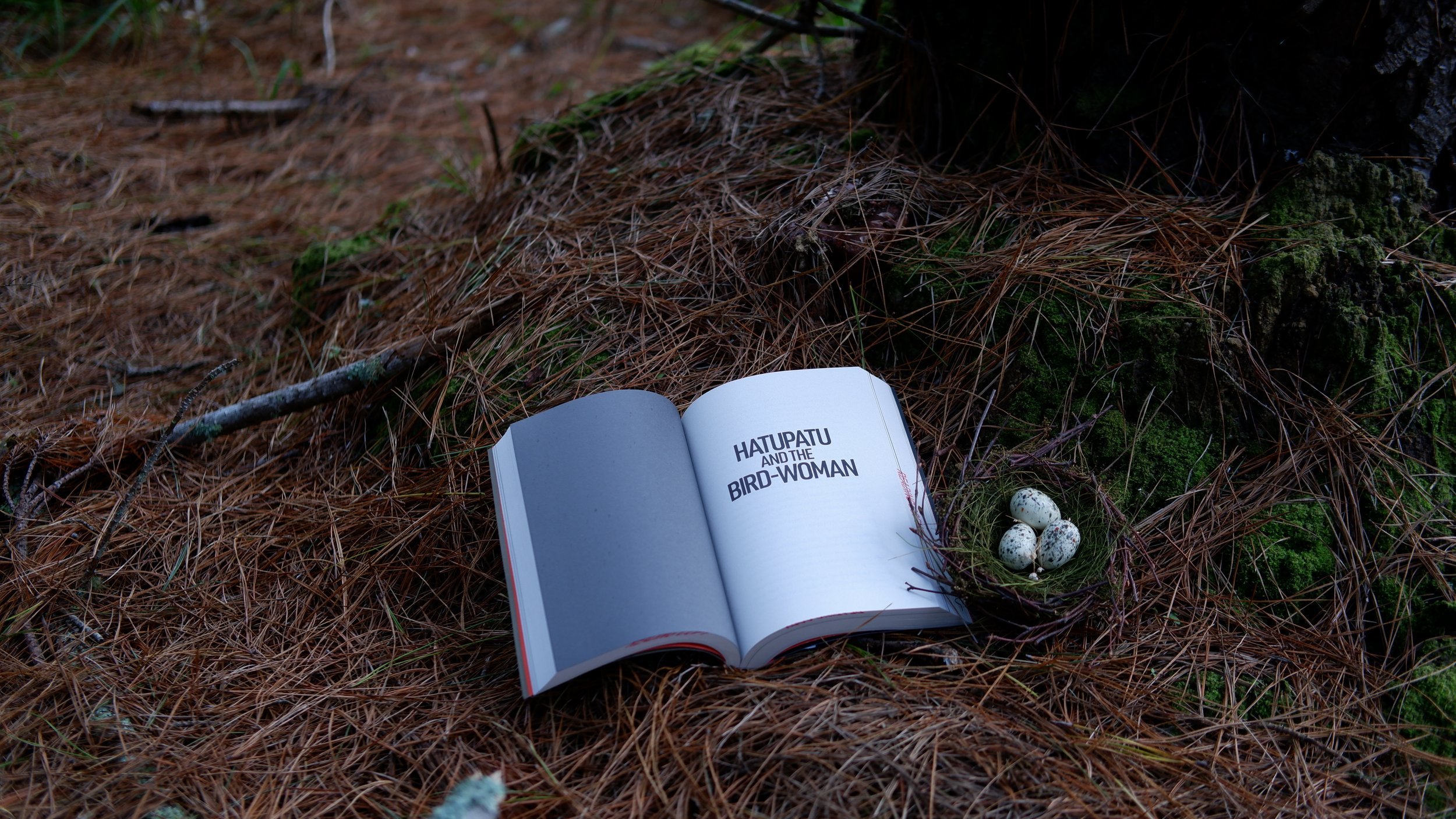

Q: There are a lot of birds throughout your retelling, do you have a favourite bird or other animal?

A: Animals I like are cats across the spectrum of big and small, otters and birds — particularly our native birds but also Secretary Birds and corvids.

Q: What inspired you to write a contemporary retelling of this popular Māori myth?

A: It is a story that I had grown up with and because I whakapapa to the area I felt close to. I’d been interested in the story from the point of view of Kurangaituku for as long as I can remember — so really I indulged my own curiosity in writing it! What often happens when I have a project bubbling away in my mind is that the protagonist’s voice will start whispering to me, so I do what you do when you meet someone new and ask them about their life and their world — so I suppose Kurangaituku inspired her own story.

Q: We know you’re also a playwright, could you explain why you decided to write Kurangaituku as a novel rather than a play?

A: There were aspects of the story that would have been awkward on stage — Kurangaituku doesn’t have a physical voice. It is also a story about reclaiming your own story and the idea of subjectivity so it needed to be told through the mind of Kurangaituku. You can do this through a first person narrative far more easily than you can do on stage. I was also interested in pushing the experience of a novel — what could I do in a novel that couldn’t be replicated in another form? I wanted to experiment with how the structure and the physical object of a book could contribute and support the narrative.

Q: Do you follow a similar process when you write a novel vs. a play?

A: I have yet to follow the same process for any of my projects! I do tend to start with a character and work out from there, but sometimes I don’t. It really depends on the project.

Q: Would you like Kurangaituku to be adapted for stage or screen? If so, are there any actors you would love to see play Kurangaituku or Hatupatu?

A: I think to be true to the novel, an adaptation would have to start with examining what are the boundaries and strengths of theatre or film — how can the story be retold that makes the form inseparable from the narrative? I haven’t thought of casting for Hatupatu or Kurangaituku. The only casting I did while writing was Whiro and Tū, and I imagined Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement from back in their Humourbeast days playing those characters.

Q: And finally, what is the main reason for the non-linear structure to Kurangaituku? Did you plan the non-linear structure from the beginning or is it something that came later?

A: I wanted the reader to experience time, deep time, the way Kurangaituku does so I experimented a lot with ways I could do that. It’s still not as non-linear as I wanted it to be! I also wanted to explore the ways that Pūrākau were told, and often that’s in a non-linear way. I particularly wanted the reader to flip the book at the points where the world of Kurangaituku has been turned upside down. The idea that it could be read from either end came fairly late — but surprisingly it didn’t take a lot to make that happen. I had already written the novel in parts, so it was just rejigging the parts “Te Kore”, “Te Pō” and “Te Whaiao” so that they echoed and mirrored each other a little more.

So… what do we think?

-

Olivia's thoughts:

I found Kurangaituku a challenging read - in a good way. The structure, pacing, rhythm and tone is unlike anything I have come across before. I was forced from the opening page to slow down, absorb, consider, and open myself up to impossibilities. In a fast-paced frenetic life, this isn’t easy to do, but it has changed my view of reading and, in the wonderful way life imitates art, has made me reconsider the role a reader plays in the storytelling process.

Whiti Hereaka has written a remarkable re-telling of a Maori myth about Kurangaituku (the bird-woman) and Hatupatu, the man who betrays her. It is deliberately non-linear, with three strands to be read in whichever order the reader chooses. One strand emerges as if from the darkness and grows bigger, brighter, and more powerful, just as Kurangaituku does. Another sinks to the depths of the underworld. The third takes a traditional path. The rhythm of the prose mirrors the story - gathering in momentum, dipping and diving - at times loud and shocking, at others quiet and melancholic. There is beauty, but more often, there is pain and death.

For me, the novel is about finding our voice, or in the case of Kurangaituku who had no voice, finding a way to be heard and, more importantly, understood. Often our perception of a person - a person we may never meet face to face - is built around the way other people talk about them. By existing through other people’s voices, that person’s story grows. So is the case for Kurangaituku.

As Whiti Hereaka says so beautifully: “Someone, somewhere, tells a story about you. In that act of storytelling, that person is not just talking about you but has actually created a you that exists in their story. You exist in this plane and in the world created by story. Both instances are you and exist independently, and more importantly, dependently.”

-

What the judges are saying:

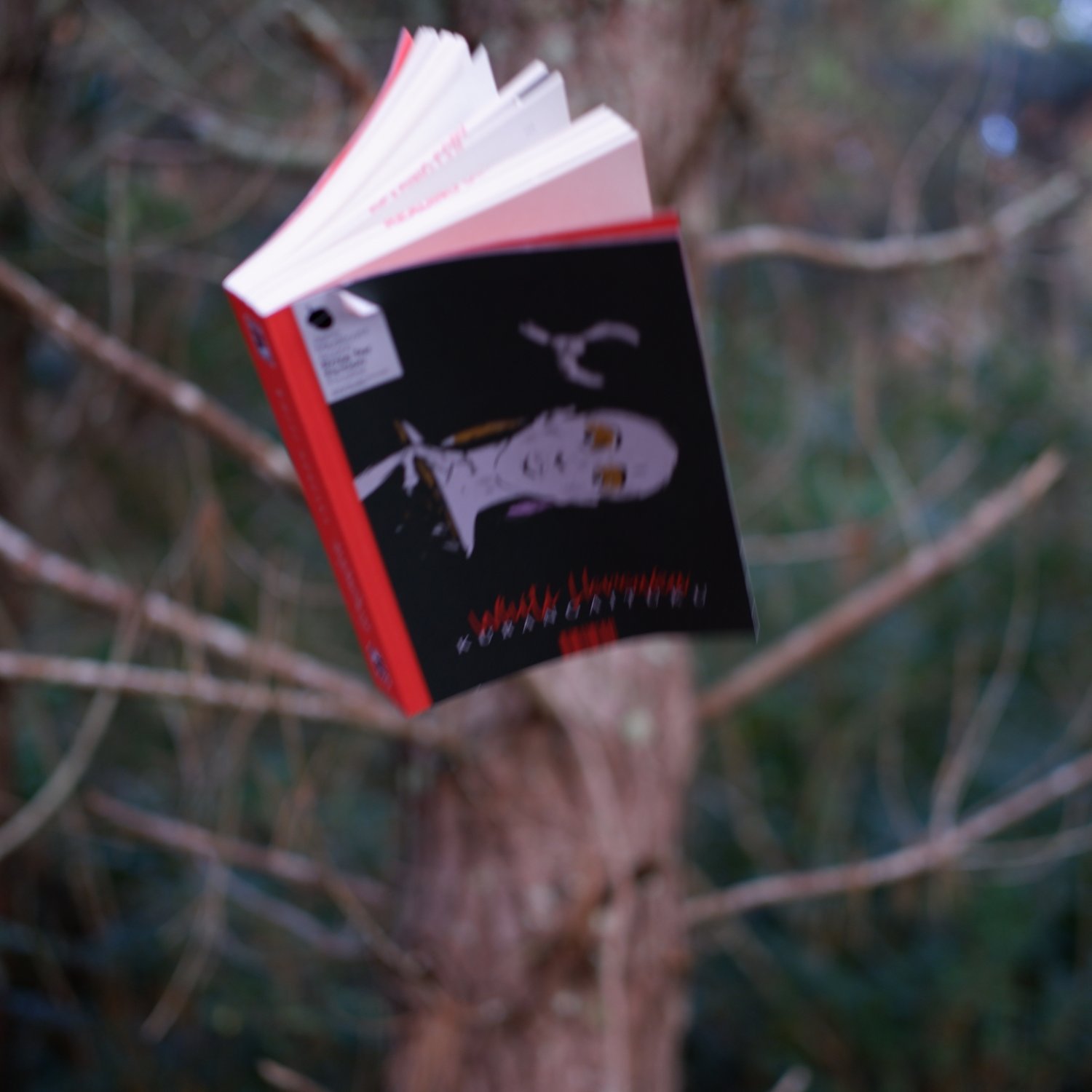

Ten years ago, Whiti Hereaka decided to begin the task of rescuing Kurangaituku, the birdwoman ogress from the Māori myth, Hatupatu and the Bird-Woman. In this extraordinary and richly imagined novel, Hereaka gives voice and form to Kurangaituku, allowing her to tell us not only her side of the story but also everything she knows about the newly made Māori world and after-life. Told in a way that embraces Māori oral traditions, Kurangaituku is poetic, intense, clever, and sexy as hell

-

Rachel's thoughts:

Can I just say that I found it super difficult to write a review for this book? It’s like nothing else I’ve ever read and for that I’m at a loss for words.

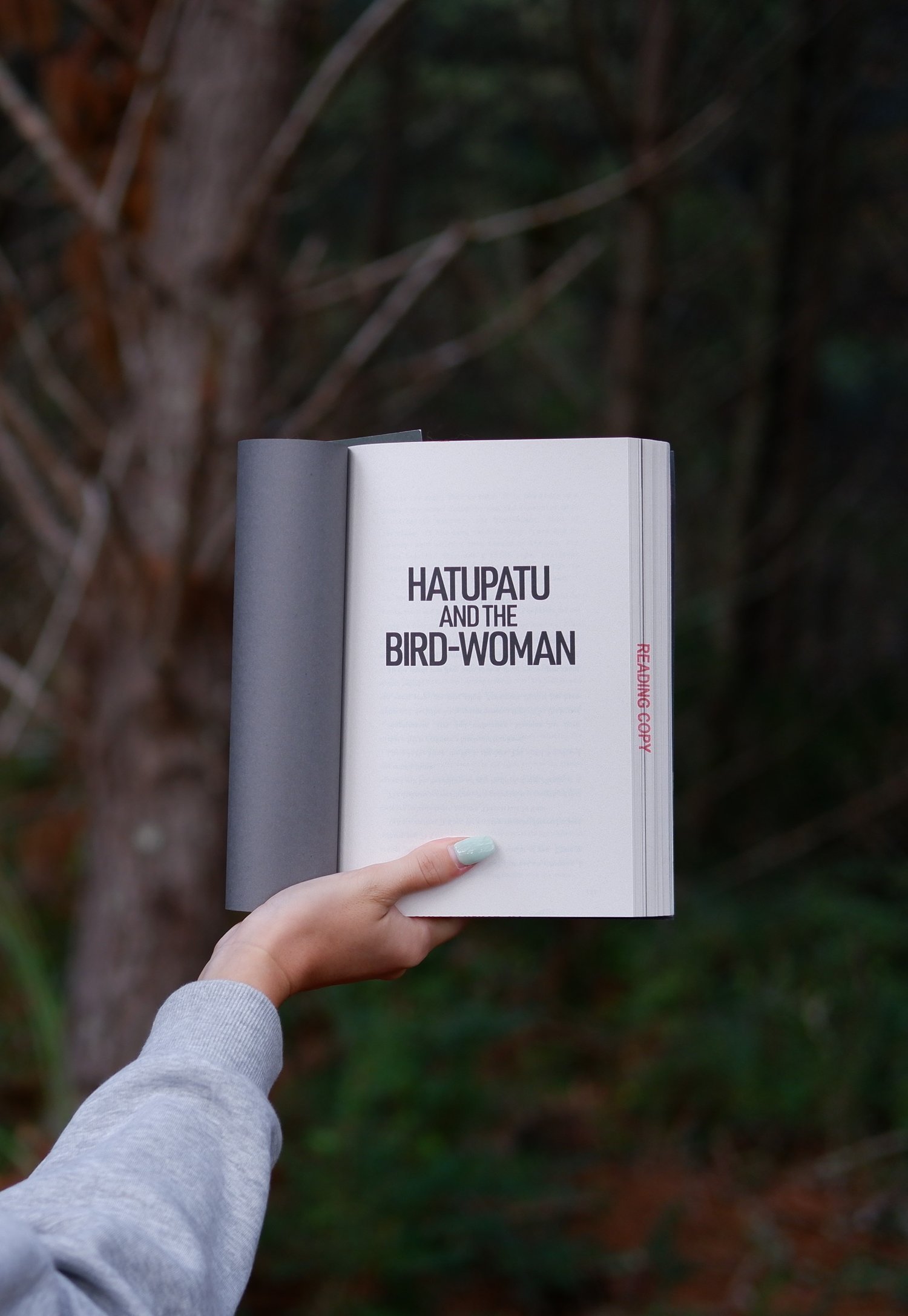

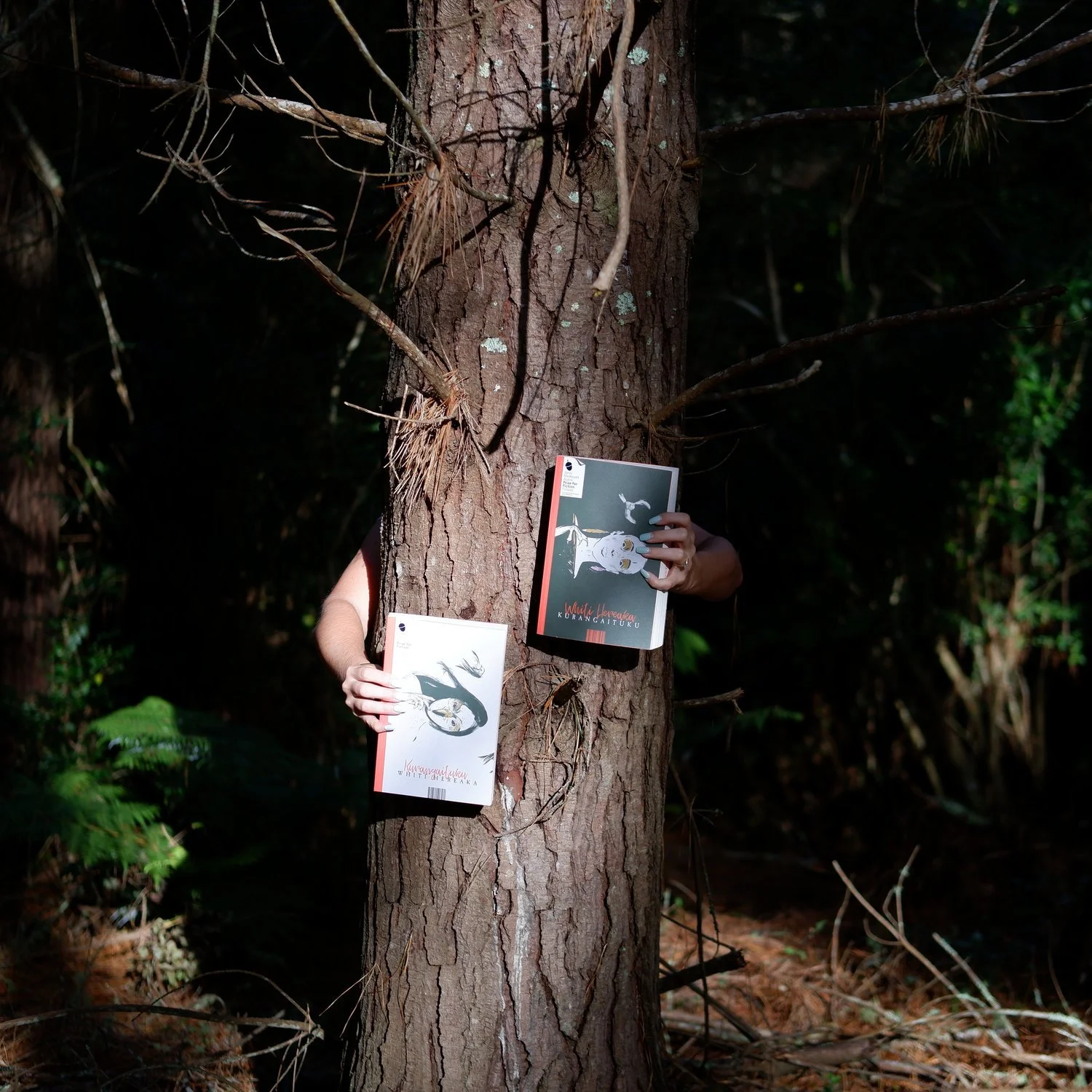

I’d like to start by saying that I’m a sucker for a pretty book. I know we’re not supposed to judge a book by its cover but with a work of art like this how can you not??? I bow down to Huia Publishing for producing these gorgeous covers. They’re not just for show either, each side represents the story inside and I have to say that that was my favourite part of this book. It is a unique reading experience. You can start with either story, the choice is up to you. I started with the light side ‘ Te Kore’ which I interpreted as Kurangaituku’s creation, then I read the dark side ‘Te Pō’ which is her journey in Rarohenga - the Māori underworld. Finishing off with the story in the middle which is Whiti’s re-telling of the ‘Hatupatu and the Bird Woman’.

This was my first introduction to the bird-woman myth. I don’t know the story of Hatupatu and I’ve never heard any versions of the myth so I went into this totally blind and I’d like to reassure you that that’s okay! You don’t need to be familiar with the characters at all, actually I’d recommend you go in forgetting what you’ve heard about Hatupatu and the traditional ‘monster’ bird-woman and start reading with fresh eyes.

I’d also like to point out that I know absolutely no Te Reo Māori but I truly enjoyed how the language is blended into the story - it creates a fascinating rhythm and lyricism. I did look up the occasional word but you can easily understand by context alone.

This is a book that I can imagine my English lecturers at university would absolutely froth over. From its non-linear structure to its sweeping prose you could study it for hours and still find more to talk about.